“Keeping Up Appearances” and the Perils of Respectability: How a British Sitcom Mirrors a Deeper Truth About Faith, Class, and Courage

In the glossy veneer of BBC costume dramas and highbrow satire, few series have endured — or charmed — like Keeping Up Appearances. Airing from 1990 to 1995, and still enjoying syndication across the globe, this quintessential British sitcom remains a comic masterclass in character, class, and human frailty. But beneath the laughter, floral china, and impeccably arranged faux-aristocratic dinners lies something deeper: a powerful meditation on the danger of obsessing over appearances — a theme as ancient as the Scriptures and as relevant as ever.

The Social Climber in Pearls: Who Is Hyacinth Bucket?

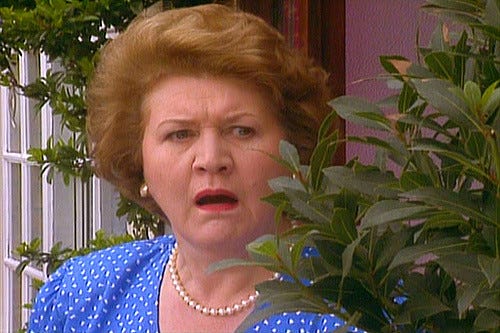

At the heart of Keeping Up Appearances is the indomitable Hyacinth Bucket (pronounced “Bouquet,” of course), played with operatic precision by Dame Patricia Routledge. Hyacinth is a woman possessed — not by demons, but by delusions of grandeur. Her middle-class reality cannot compete with her high society fantasies, and so she constructs a world where she is queen of the cul-de-sac, hostess of candlelight suppers, and wife of “a man with a good position in the council.”

Her long-suffering husband, Richard (Clive Swift), is dragged through endless social charades, enduring everything from absurd tea parties to yacht-themed goodbyes, often with a sigh and a stoic grimace. Their dynamic — she, determined to impress everyone; he, desperate to go unnoticed — is as funny as it is tragic.

But the real genius of Keeping Up Appearances lies not just in the antics, but in what they reveal: the British class system’s unspoken codes, and the emotional toll of trying — and failing — to transcend them.

The Appearance of Respectability as a Mask

Hyacinth’s world is one where respectability is currency, where appearances dictate worth. Her desperation to avoid her working-class sisters (especially the delightfully disheveled Daisy and the sultry Rose), and her tireless efforts to mingle with the genteel elite, are played for laughs. But the joke cuts deep.

In a society still marked by class consciousness, Hyacinth’s behavior exposes the insecurity and shame that often underlie social mobility. She isn’t just pretending for fun — she is trying to rewrite her identity. To be seen, to be respected, to be loved — not as she is, but as she imagines she should be.

And it’s not a uniquely British problem.

When Comedy Meets Scripture: A Pauline Parallel

The absurdity of Hyacinth’s struggle finds a sobering echo in the New Testament. In his letter to the Galatians, St. Paul warns against those “determined to keep up outward appearances so that the Cross of Christ may not bring persecution upon them.” For Paul, the true danger of pretending — of conforming to human expectations while abandoning divine truth — is spiritual death.

This same conflict underpins Keeping Up Appearances. Hyacinth lives in fear of being exposed — not for a crime, but for her reality. Her identity is so wrapped up in how others perceive her that she loses touch with who she truly is. It is the spiritual equivalent of building a house on sand.

Yet her story is not far from our own. In today’s world, where social media platforms encourage curated lives, and where traditional Christian values are often mocked in elite circles, the temptation to blend in — to “just say the words” — is immense.

Respectability Versus Fidelity: Lessons From History

There are countless real-world Hyacinths — individuals who mold themselves into what society wants to see. But then there are those who do the opposite: the ones who resist appearances and live faithfully, even at great cost.

Cardinal George Pell, who endured a high-profile legal battle with grace and resilience, is one such figure. So is Paivi Räsänen, a Finnish MP facing prosecution for expressing her Christian convictions on marriage. Neither sought controversy, but both refused to betray their conscience to maintain societal respect.

Their courage echoes that of martyrs past. St. Thomas More, who refused to approve King Henry VIII’s divorce, and Blessed Franz Jägerstätter, who would not swear allegiance to Hitler, both chose truth over safety. In each case, friends and family urged them to simply “go along,” to maintain appearances. Their refusal cost them everything — except their souls.

Comedy as Cultural Mirror

That a sitcom could serve as a gateway to such moral questions is a testament to the brilliance of Keeping Up Appearances. While the BBC has, in recent years, come under criticism for perceived ideological bias and a drift from traditional values, this series stands as a glowing example of what public broadcasting can do when it puts storytelling first.

Through laughter and cringe, Keeping Up Appearances offers more than a send-up of suburban snobbery. It invites viewers to ask: What am I hiding? What mask am I wearing to be accepted? And perhaps most importantly: What am I sacrificing at the altar of appearances?

In a time when being authentically Christian can be a career liability in media, politics, and academia, Hyacinth’s antics feel prophetic. Her obsession with external validation mirrors the world’s growing discomfort with sincerity — especially religious sincerity — in the public square.

The World Upside-Down: Saints and Sitcoms

As G.K. Chesterton once wrote, saints are those who make the world “stand on its head.” In their defiance of worldly norms, they show us how absurd our values have become. Hyacinth, in her own way, does this too — albeit unintentionally. She reveals just how shallow respectability can be, how silly our social games, and how desperately we cling to illusion.

The saints, however, offer an alternative. They live not for appearance but for truth, not for approval but for love. They remind us that faith, like comedy, often involves risk — the risk of being misunderstood, ridiculed, or even rejected. But it’s in that risk that integrity is born.

Final Curtain Call

As reruns of Keeping Up Appearances continue to delight audiences worldwide, let’s laugh — but also listen. Beyond the perfectly polished silverware and disastrous garden parties lies a challenge. Are we keeping up appearances? Or are we keeping the faith?

The sitcom may be over, but the questions it raises are eternal. And the answer, as always, lies not in the bouquet, but in the Cross.